Officials warned Uyghur residents they could face detention for listening to unapproved music, as scholars say the campaign reflects expanding efforts to control cultural expression.

A poem written inside a prison cell has become one of the songs Chinese authorities now warn residents not to hear.

In a leaked political study session from Yengisar County in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which many Uyghurs refer to as East Turkestan, officials listed the track among more than “120-plus songs” deemed problematic — underscoring how cultural expression has increasingly been treated as a matter of state security.

The recording was shared with Uyghur News Network by the Norway-based Uyghur human rights organization Uyghur Hjelp and later published in full translation by Kashgar Times.

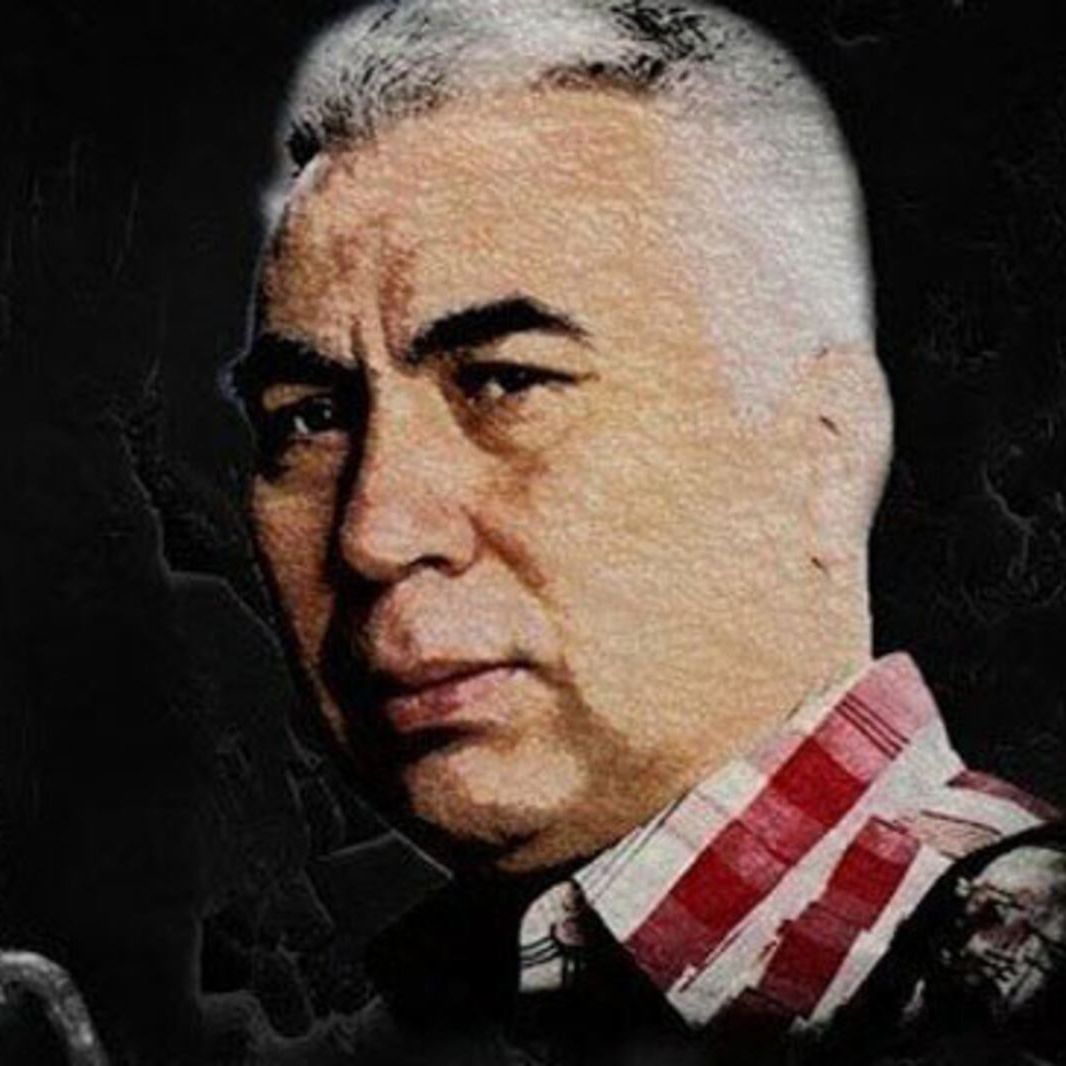

Abduqadir Jalalidin, a Uyghur poet and literature professor, was detained in 2018 amid a broad security campaign in the region. It was during his detention, according to those familiar with his work, that he composed the poem later known as “No Road Home.” Smuggled out, the verses traveled across borders, where a Uyghur musician in exile set them to music — transforming a private reflection written in captivity into a song now heard among diaspora communities.

“Yet all in vain I receive no news from the blossoms and flowers,

No Road Home

This yearning pain has seeped right through to the marrow of my bones —

What is this place I have come to, when I am left with no road home?”

Abduqadir Jalalidin

Translated from Uyghur by Uyghur American poet Munawwar Abdulla

The journey from prison cell to banned recording illustrates the widening reach of a campaign that scholars say is reshaping cultural life in the region.

During the session, authorities grouped songs into seven categories they described as dangerous, including works said to “twist history,” promote religion, encourage separatism, or undermine social stability.

Officials instructed attendees to delete such music from their phones, avoid downloading unapproved tracks, and report violations to police. Examples were cited of residents detained for up to ten days under China’s Anti-Terrorism Law after sharing songs on social media platforms.

Even as the session outlined sweeping restrictions, an official sought to minimize their scope, saying Uyghurs have “a few thousand songs” and that the government was banning “only 120-plus songs.”

Yet scholars say the breadth of the categories — spanning references to homeland, language, family, and faith — suggests enforcement may not be tied to a fixed list but to flexible definitions that can expand with shifting political priorities.

Jalalidin is among many Uyghur writers, scholars, and cultural figures detained as authorities expanded incarceration across the region beginning in 2017. Researchers and rights groups estimate that more than one million Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples were held in detention facilities described as internment camps. Hundreds of prominent intellectuals are believed to have been imprisoned. The details of Jalalidin’s sentence and current place of detention have not been publicly disclosed. Scholars say the crackdown has reshaped the region’s intellectual life, with literary voices silenced and Uyghur-language publishing significantly curtailed.

Scholars say the inclusion of a prison-written poem on the banned list offers insight into how authorities increasingly view artistic and cultural life as a political concern.

“Banning songs is nothing new in China. Throughout the period of CCP rule to a greater or lesser degree depending on the political climate, Uyghur songs, poems and books have been censored and banned and their authors and performers have been persecuted or imprisoned for their work,” said Rachel Harris, a professor of ethnomusicology at SOAS University of London, who told Uyghur News Network.

What makes the document notable, she said, is the range of material it targets.

“This new document listing banned songs is very interesting for a few reasons. It includes a wide range of songs, from very well known folk songs that mention the name of Allah, to songs recently produced abroad that address the ongoing persecution of Uyghurs in their homeland, like Yanarim Yoq [No Way Home]. I was amazed to see that song in the list. It actually gave me some hope because it shows that people in the homeland can access the voices in the diaspora.”

For some researchers, the breadth of the ban may reveal less about cultural compliance than about official concern over what remains beyond state control.

Anthropologist Rune Steenberg, who researches the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Uyghurs and Central Asia, said the campaign reflects what he views as an effort to exert tighter control over cultural production in the region.

“I think that the Chinese government is trying to take full control of the cultural production in XUAR,” Steenberg told Uyghur News Network.

Songs, he added, carry particular weight.

“The songs are carriers of memory and must therefore be limited or controlled.”

Steenberg said authorities often interpret expressions of identity through an escalating security lens.

“The songs are seen as signs for Uyghur national pride which is then seen as a sign of nationalism which is then seen as a sign of separatism.”

Yet scholars say the very need to police songs may point to the limits of cultural control.

“I think this list shows that in spite of the extreme intensity and brutality of the campaigns they could not fundamentally change Uyghur society,” Harris said.

Be First to Comment